Music Iconography in L’Illustration (Paris 1843-1899)

Prefatory Remarks

Music iconography in the nineteenth-century illustrated press constitutes an extensive and remarkably rich documentary resource for the music historian. Yet, with one major exception, the three-volume work published in 1982-83 entitled Les gravures musicales dans L’Illustration (Paris, 1800-1899)[1], it remains largely unexplored. Addressing this lacuna, the L’Illustration volumes offered a methodology for rendering such sources accessible by providing a comprehensive locator catalog (two volumes) reproducing some 3500 engravings of musical interest and an extensive critical apparatus (one volume) including (i) a detailed analytical index, (ii) several appendices[2] (one of which contains a listing of article titles in which the engravings appear, and a listing of all visual artists (dessinateurs, engravers, photographers, artists, sculptors and their respective works).

The printed volumes received much positive critical attention[3] while recognizing the importance of this monumental, largely unexplored corpus of primary source material. However, at the same time, we must recognize that since the print publication some forty years ago, little attention has been devoted to the study of this type of documentation, and even less, to making it available in a structured, comprehensible manner. No doubt the complex problem of controlling bibliographically such a vast amount of documentary material has contributed to its neglect, as has the limitations of print publication. Clearly, the undertaking would have been better served if it had appeared in a digital format. But at that time the cost of storage space and delivering high quality grayscale images was prohibitive. So... this time, some forty-five years later, we try again, but in a digital format while acknowledging RIPM’s support of this extensive undertaking.

Within a fourteen-month period, 14 May 1842 to 1 July 1843, a major illustrated newsmagazine appeared in three European music capitals: The Illustrated London News(London, May 1842); L’Illustration, journal universel (Paris, March 1843)[4]; and Illustrirte Zeitung (Leipzig, July 1843). What is exceptional about these publications is that they include depictions of contemporary activities (often in great detail) during a period in which there was a very active musical life.

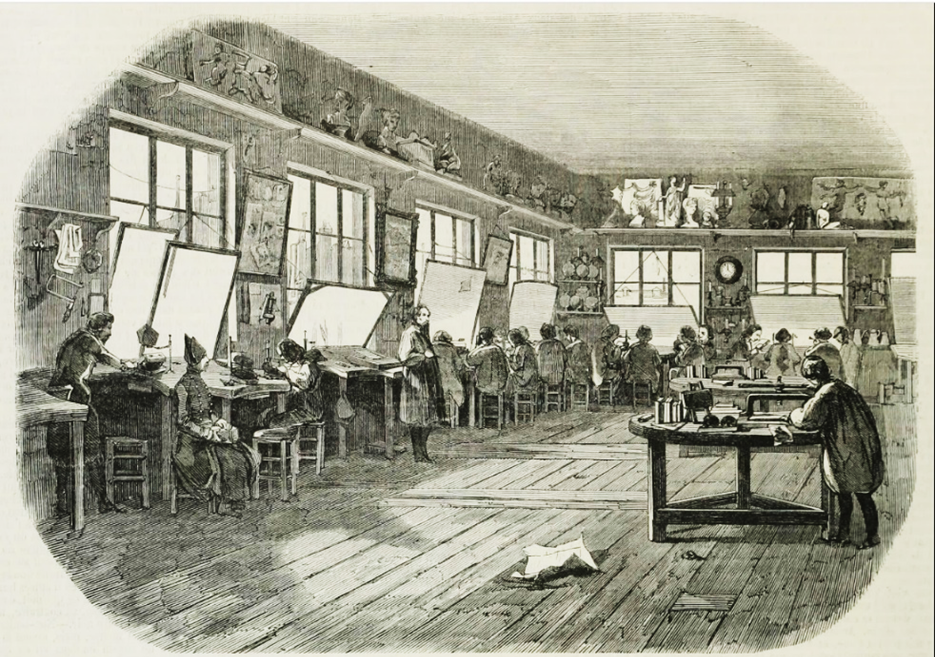

Why did the first journals to produce illustrations of contemporary events appear suddenly in the early 1840s? Largely because of two interrelated discoveries: one, the development of techniques that permitted multiple engravers to work simultaneously on the same engraving. And two the discovery that large slices from the trunk of boxwood trees could serve as plates for printing engravings in newspapers. The process was straight forward. An image was sketched on to a boxwood slab. This plate with the sketch was then cut into pieces, each with a different portion of the design. The pieces were then distributed to different artisans, each of whom worked simultaneously to engrave “their” part of the image. Finally, the engraved smaller blocks were fitted together to create a single plate reflecting the complete original design.

Obviously, this process greatly increased the speed at which engravings could be executed and printed. Before this period, the length of time required to prepare an engraving for printing simply excluded the possibility of depicting current events in a timely manner. Yesterday’s news was no more interesting then, than it is today.

The readers of the 1840s were the first to be treated to illustrations depicting the latest news reported in the press. It is easy to imagine that this development led to a phenomenal number of new illustrated publications treating a large variety of subjects. It also likely led the Parisian opera-lovers of the mid-1840s to expect to read, perhaps with the morning café and croissant, not only a print review of a first performance of a new opera, but also to marvel at depictions of its magnificent scenery, mise-en-scène, and singers in costume.

L’Illustration

Long recognized for the quality of its engravings,[6]L’Illustration is generally considered “the technical success of the illustrated press.”[7] Its overall excellence has long been recognized: “It is the most beautiful and the most important of the illustrated periodicals, as much in France, as elsewhere”;[8] “Its reading constituted a sort of praiseworthy social act”;[9] “L’Illustration, that beautiful and important publication which obtained so great a success... trained a large school of talented dessinateurs and engravers in this genre”;[10] “L’Illustration was during more than a century the illustrated French magazine of quality...”[11] Moreover, the significance of its iconographical repertory was recognized over one hundred years ago, in the article devoted to the journal in the Larousse Grand Dictionnaire universel du XIXe siècle. Depicting current events both by the pen and the drawing “was in effect an excellent idea,” the article noted, for “the drawing thus became an instrument of historic conservation.”[12]

The preface to the journal’s 1 September 1843 issue described its aim. L’Illustration will truly be

A vast inventory which will recount and illustrate, in their turn, all the facts that contemporary history registers in its annals... L’Illustration will be, in a word, a faithful mirror which will come to reflect, in all its wonderful activity and so varied animation, the life of society in the 19th century.[13]

With respect to the musical life of the period, the first French illustrated newsweekly proceeded, in large part, to satisfy that goal. In fact, the preface to L’Illustration’s very first issue promised that special attention will be accorded to the arts in general and to the theatre in particular.

All the news of politics, war, industry, manners, theatre, fine arts ... are of interest to us...

Let us immediately consider the theatre; here our intention, instead of simply analyzing the plays, is to depict them. Actors’ costumes, groups and stage designs in the principal scenes, ballets, dancers, everything belonging to that art where the pleasure of the eyes holds such an important place; [Théâtre-] Francais, Opéras, Cirque-Olympique, small theatres, everything from everywhere will be reflected in our reviews, which we will try to illustrate so perfectly that the theatres, if it were possible, would be forced to criticize us, claiming that we are competing with them by offering our readers real shows in an armchair.[14]

L’Illustration published between 1843 and 1899 some 3,350 engravings of musical interest which offer a veritable visual history of the musical activities of the period. Architectural designs, interior and exterior views of concert halls and opera houses; mises-en-scène, scenery and costume designs of operas and ballets; representations of theatrical companies and portraits of composers, performers, conductors and critics; instruments and instrument makers; ceremonies, exhibits, festivals, fairs, gala performances and concerts in halls, salons and in the open air—these are but a few of the subjects depicted, and in some cases, caricatured.

But to what extent do the engravings in the journal faithfully represent that which they depict; to what extent are L’Illustration’s engravings instruments of “historic conservation”? One must keep in mind that L’Illustration was a newsmagazine—in terms of present-day comparisons perhaps a cross between L’Express or Time Magazine and Paris-Match or Life Magazine. The primary function of L’Illustration was to chronicle the news, both visually and textually. This does not mean, however, that every musical element was accurately represented. A clarinetist—in an obscure corner of a tiny engraving depicting numerous activities at a village festival—playing his instrument with his right hand placed above his left, should neither lead one to “discover” a curious contemporary performance practice, nor to conclude that the majority of L’Illustration’s engravings are inaccurate. Such anomalies do exist, but one must consider them within the general context in which they are presented. When musical elements of an engraving are clearly of secondary importance, attention to their faithful representation is not always present. However, when an aspect of the musical life of the period is either the principal subject or an important element of an engraving, considerable effort to depict it accurately appears to be the rule. For example, surviving musical instruments and buildings allow us to verify how faithfully they were reproduced, and early photographs to demonstrate how carefully the engraved portraits were drawn. Furthermore, research dealing with the staging of 19th-century opera[15] has revealed that even the most minute details of set designs, costumes and the positions of performers on stage were faithfully represented in L’Illustration —a fact, moreover, recognized by the journal’s contemporaries.[16]

Our intention is to present a comprehensive Catalogue of all engravings dealing with musical activities published in L’Illustration during the 19th century, and to complement the Catalogue with an appropriate Critical Apparatus. The philosophy motivating the selection of engravings can be stated simply: almost all visual elements relating to musical life—whether a tiny representation of a musical instrument in a corner of a painting, a part of the interior decoration of a concert hall, a single snare drum in a battle scene, the exterior of a musical instrument factory, an advertisement for a piano, an elaborate mise-en-scène or a portrait of Berlioz—all are accounted for in this work.[17]

The Digital Edition

Perhaps the greatest difference between the two editions is the far superior quality of the digital images when compared with those in the printed locator catalogue. Scanning at a fairly high resolution obtains excellent digital reproductions of wood engravings, which, even when compared to the original in the press often add a wonderful depth to the images, not visible in the original. Also significant is the analytical index discussed below.

Manipulation of the images

When one clicks on an image, the symbols in this box appears beneath it. Clicking on the first symbol (reading left to right) increases the size of an image, while clicking on the second, reduces its size. One can also select the previous and next image, enlarge an image to full screen or reduce its size. The symbol in the middle permits one to display an image at a higher resolution. One can also capture a screen shot of the entire image or a part thereof, and save it to a computer. The images can also be published with recognition of the RIPM database from with they were extracted.

Searching

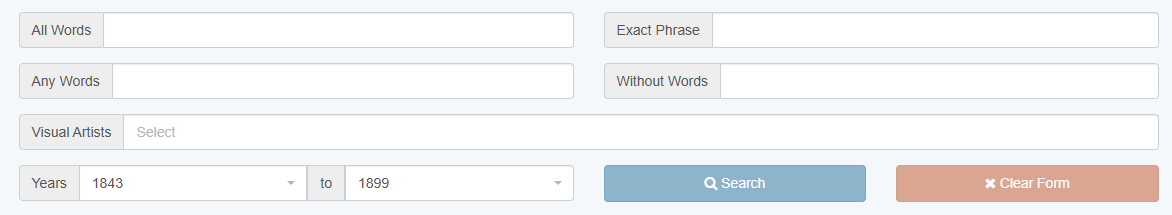

There are two search modes: Basic and Advanced. They may be searched in either English or in French.

Basic search offers a single search window that searches four fields:

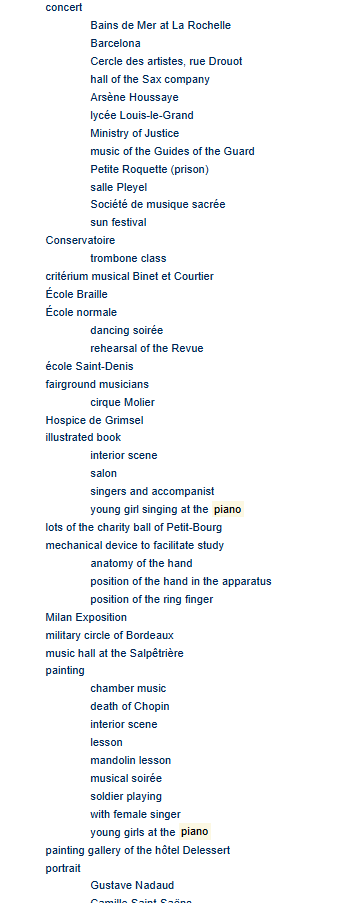

- Search visual content of images: includes text and descriptive keywords. This produces all images related to the search query, presented in chronological order.

- Subject index. This permits the user to view the detailed “printed” index with a number of advantages offered by digital publication.

- Search titles of articles in which engravings appear.

- Search for the names of works by visual artists: engravers, photographers, dessinateurs, painters, sculptuors, and photographers.

Basic Search

Hover over or tap on the yellow boxes for a description of the field.

Advanced Search adds Boolean delimiters

Search Results

Taxonomy

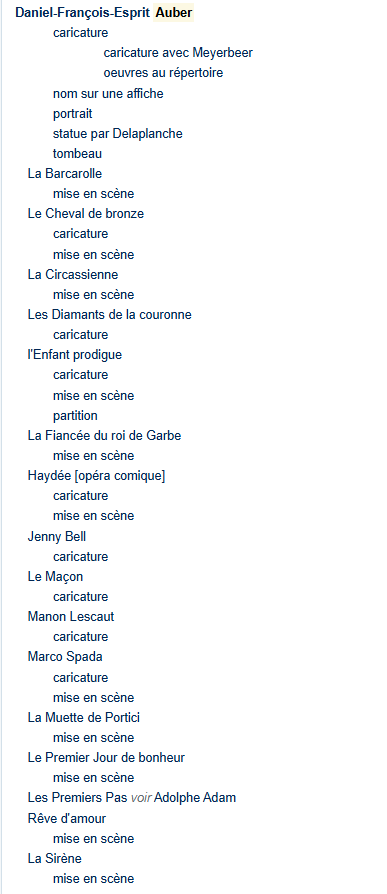

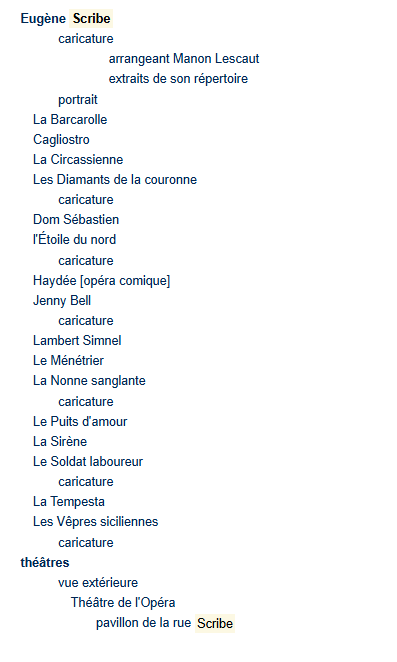

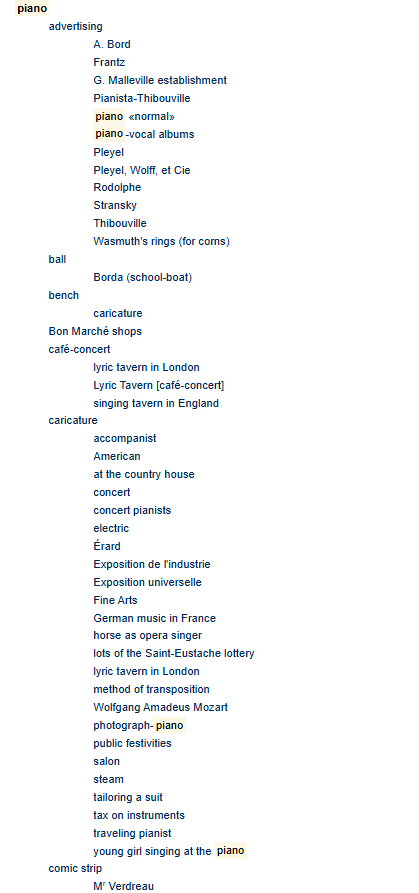

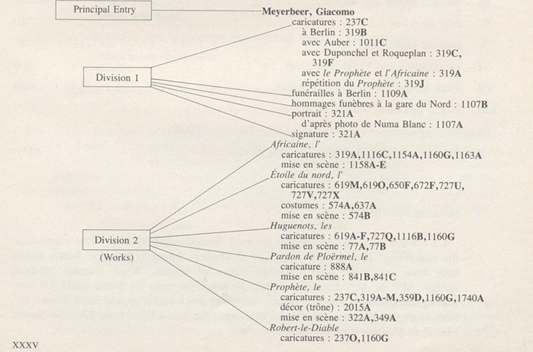

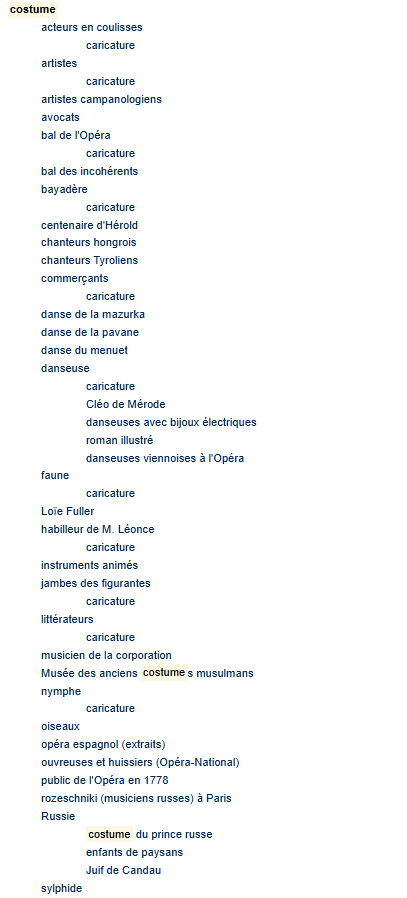

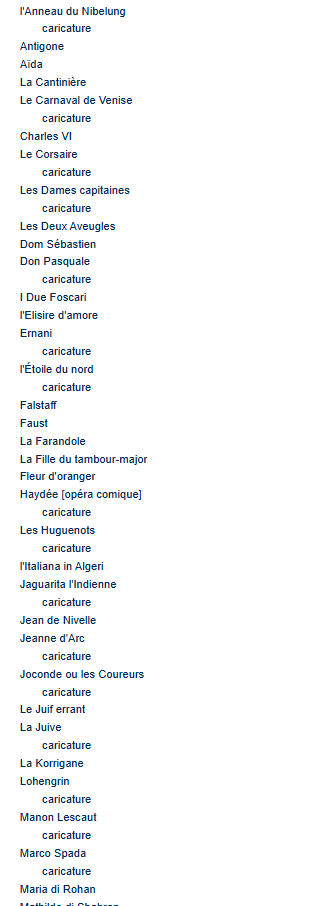

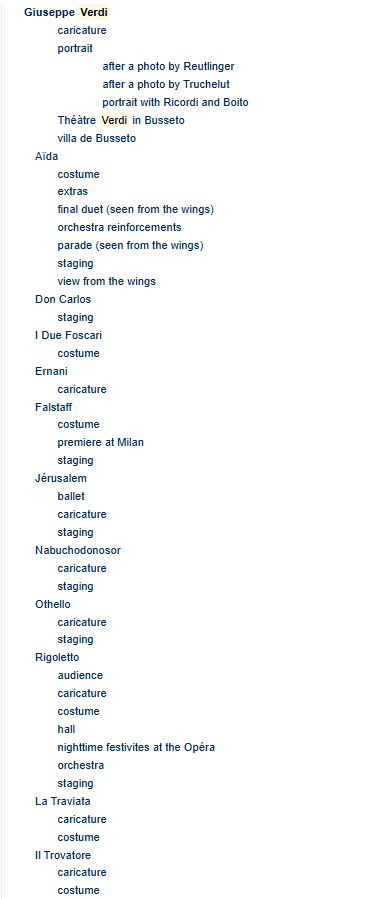

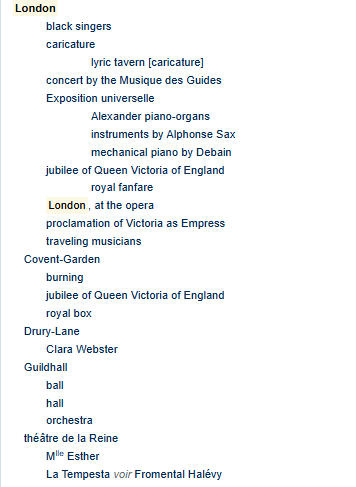

The structure of the index (is somewhat original).

As the indexing progressed it became apparent that isolating one important element from the many relating to a single subject heading offered, in a large number of cases, a more clearly focused structure and one more easily comprehended by the reader. Thus, frequently, entries listed beneath a subject heading are divided into two groups, the first dealing with many elements (presented alphabetically), the second dealing with a single element (also presented alphabetically). And, as above, the entries within each division may possess an additional indexing level, as required. (Division of related materials into two groups and use of the additional indexing level depend upon principles established in the course of the preparation of the Index and codifies in the thesaurus.) While in most cases the element dealt with in the second division will be self-evident, information concerning the division of elements delating to specific subject headings is given below. Fortunately, the result is less complicated than its description.

Six examples below demonstrate this structure: two deal with composers, one with a librettist, one with keyboard instruments and one with a city.

| Principal Entry | Division I | Division II |

| individuals

authors of dramatic works choreographers composers librettists scenery designers translators |

general entries |

titles of works created |

| Principal Entry | Division I | Division II |

| Name of instrument, for example

clavecin piano trombone violon |

general entries |

company manufacturing instrument, model of instrument or instrument maker description of illustration |

The entry for Meyerbeer reproduced below illustrates the application of this procedure. Division one, indented six spaces, deals with all subjects except Meyerbeer’s operas which are dealt with exclusively in division two, indented two spaces.

| Principal Entry | Division I | Division II |

| Name of instrument, for example

costumes décors mise en scène violon |

general entries |

titles of works description of illustration |

Appendix

Reviews of the Print Edition

“A monumental reference work...a model for all such endeavors.”

“The much-awaited reference work that all 19th-century scholars must acquire.”

“The collected documentation is remarkable...a model of methodology.”

“A monumental collection of documents containing such a profound wealth of material has never before appeared...With this publication a treasure threatened with being totally forgotten is brought to light...One cannot praise highly enough this enterprise.”

“Importantissima opera...the social and cultural function of music emerges clearly from the pages.”

“An undertaking without precedent...one sees the century unfold...an exemplary success.”

“Certainly a book for the reference shelves...”

“[A] giant undertaking...anyone involved in work with the 19th-century will need this unique catalogue.”

“An unbelievable gold mine of information...a methodological model...one cannot describe this wealth of documentation...which surpasses one's imagination...this is an absolutely indispensable reference work which should be in every library.”

“The fact that illustrated magazines can be very significant sources for musical historical issues is confirmed...the result is impressive...should not be missing in any reference library.”

“The seminal study of this periodical.”

The great originality of this collective enterprise is the use of hierarchical indexing (presented in the form of a schema in a computer system that organizes this information ‘according to a multiple classification and at several levels...’ It should be noted that the reviews of these three volumes are at the same time very laudatory regarding the originality and the usefulness of such a tool, [and] on its documentary richness ... It is considered a model of its kind.”

“If, as the saying goes, one picture is worth a thousand words, this publication must be worth well over three million...because of the extraordinary bibliographic/iconographic controls developed...and because in this publication the whole exceeds by far the sum of its 3,350 individual parts...a panorama of music life in France...[a] remarkable chronicle...The bibliographic controls of the visual images reproduced in this publication...is a brilliant demonstration of logical organization over extreme complexity...a model...”

References

[1]Les Presses de l'Université Laval, Québec, 1982-1983. Published under the auspices of Le Répertoire international d’iconographie musicale, with a preface by Barry S. Brook.

[2] The Appendix of unidentified signatures in engravings, and the Supplement listing engravings containing musical elements of minor importance are not included in the digital edition.

[3] See, Appendix which contains a bibliography of published reviews and commentary dealing with the print publication.

[4] The journal was founded by V. Paulin, Adolphe-Laurent Joanne and Edouard Charton. It was directed from 1860 to 1886 by A. Marc, and from 1886 to 1903 by Marc’s son, Lucien. Thereafter, René Baschet directed the journal, for over forty years, until it ceased publication in August 1944.

[5] A depiction of the journal’s “atelier de gravure” in 1844 is reproduced in Claude Bellanger’s Histoire générale de la presse frangaise, 3 vols. (Paris, Presses Universitaires de France, 1962), II, p. 305. According to Pierre Gusman, L’Illustration’s original engraved wooden blocks were destroyed: “ils alimentérent le foyer des chaudières de l’imprimerie. Seuls, quelques bois de Lepre furent épargnés.” La Revue d'art ancien et moderne, 222 (January 1921), 111.

[6]“L'Illlustration... obtint, surtout par le soin donné aux gravures, un succés mérité.” William Duckett, ed., Dictionnaire de la conversation et de la lecture (Paris, Firmin-Didot, 1883), suppl. IV, p. 315.

[7] Bellanger, op. cit., IL, p. 300. LXI.

[8]Nomenclature des journaux et revues en langite francaise paraissant dans le monde entier (Paris: Argus de la Presse, 1926-1927), p. 119. For documentation demonstrating the consistent popularity of the journal, see comparative print run charts in Pierre Albert, Gilles Feyel and Jean-Francois Picard’s Documents pour histoire de la presse nationale aux XIXe et XXe siécles, édition revue et corrigée, Collection Documentation (Paris: Centre national de la recherche scientifique, 1979).

[9] Bellanger, op. cit., III, p. 387.

[10] Ambroise Firmin Dipot, Essai typographique et bibliographique sur l'histoire de la gravure sur bois (Paris, Firmin Didot fréres et fils, 1863), col. 283. Bertall, Cham, Janet Lange, Marcelin, Edouard Renard, Henri Valentin, and Jules Worms are among the many celebrated dessinateurs who worked for L’llustration.

[11]La France, les Etats-Unis et leurs presses (Paris, Editions du Centre national d’art et de culture Georges Pompidou, 1976), p. 111.

[12] Pierre Larousse. Grand Dictionnaire universel du XIXe siècle (Paris, 1866-1876), s.v. ‘'L’Illustration.”

[13] “Notre but” [preface], L’Illustration 1, 1 (4 March 1843), p. 1.

[14] Ibid.

[15] See H. Robert Cohen, “On the Reconstruction of the Visual Elements of French Grand Opera: Unexplored Sources in Parisian Collections,”’ Report of the Twelfth Congress of the International Musicological Society, Berkeley 1977, op. cit., pp. 463-480. Further evidence of the journal’s attention to faithful reproduction is offered by a systematic comparison of Paul Lormier’s costume designs (Bibliotheque de l’Opéra, D16 (8 à 16)) and their reproduction in L’Illustration.

[16] Louis Palianti (1809-1875), the author of over 200 staging manuals for works performed primarily at the Opéra-Comique and the Opéra, refers his readers, on occasion, to the journal. Palianti’s transcription of the original mise-en-scéne of Donizetti's Dom Sébastien, contains (p. 58) the following remark concerning the Act III finale: “*Le journal L’Illustration, rue de Seine 33, donne, dans son numéro 39, du samedi 25 novembre 1842, a la page 201, une magnifique gravure sur bois [see volume I, 39D, of the present Catalogue] qui reproduit trés exactement l’ensemble de la décoration, la position des personnages et des masses pendant ce finale, et les divers costumes des artistes, des choeurs, des comparses, etc., etc.” For similar remarks, see Palianti’s staging manual for Auber’s Marco Spada, p. 16 (Copies of both volumes are found at the Bibliotheque de |’Association de la Régie Théatrale (Paris). Music critics as well cited engravings in the journal. Joseph D’Ortigue, for example, in his 10 July 1864 Journal des débats feuilleton—which deals in part with “les clavecins d’Anvers”—refers to L’Illustration’s depiction of a Ruckers harpsichord (see volume I, 785B, of the present Catalogue).

[17] Representations of dance and dancers are included when there is an obvious or strongly underlying musical element, for example, ballet scenes, engravings of noted dancers, illustrations of dance steps and movements, and any depictions of dancing in which instruments are present.